"The law no longer knows white, nor black, but simply men."

The dashed hopes that re-imprinted racial identity on American culture

The last thing formerly enslaved families wanted in 1866-1867 was a Black Nation or a Black Identity. They wanted citizenship. They wanted recognition of their basic humanity and a new partnership going forward.

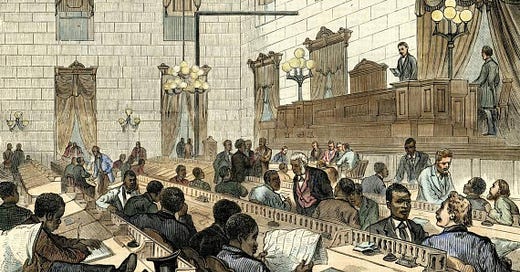

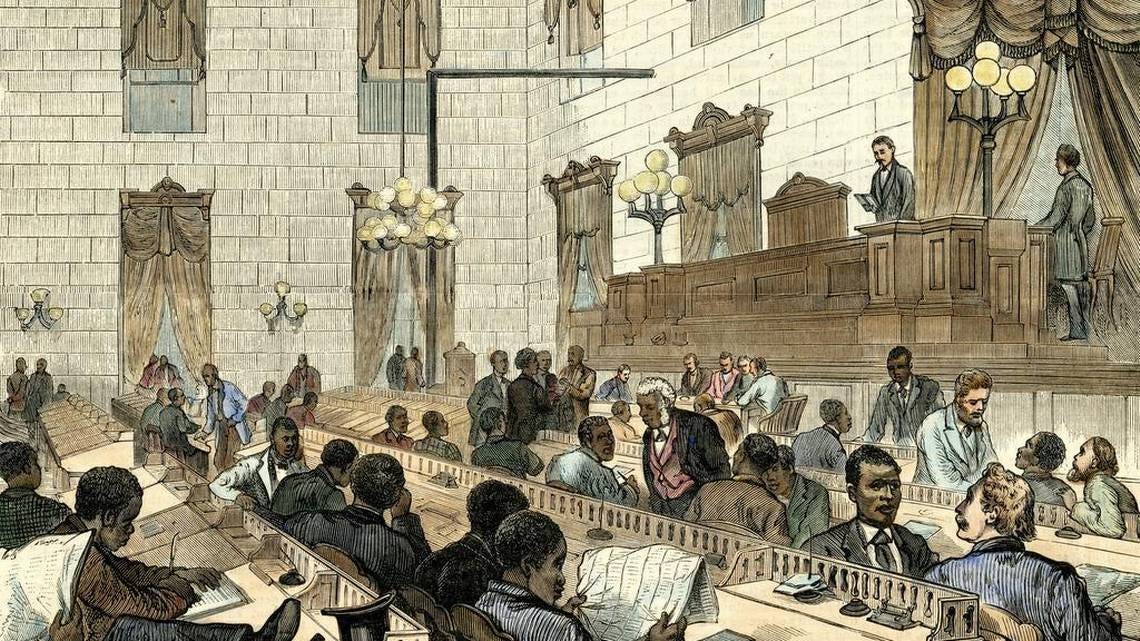

A Union League convention in Alabama affirmed "The law no longer knows white, nor black, but simply men." On that basis, "We claim exactly the same rights, privileges and immunities as are enjoyed by white me -- we ask nothing more and will be content with nothing less."

A teacher named Robert G. Fitzgerald recorded in his diary, "I heard a white man say, today is the black man's day, tomorrow will be the white man's. I thought, poor man, those days of distinction between colors is about over in this (now) free country."

Martin R. Delany, later recognized as "the father of black nationalism," had held the highest commissioned officer rank of any man of his complexion during the Civil War, serving as a major in the 104th US Colored Infantry. As a South Carolina Republican Party organizer, he "found it dangerous to go into the country and speak of color in any manner whatsoever." The danger, at that point in time, was not from South Carolina's "white" minority, but from the darker-skinned majority of the state's population, who told him "We don't want to hear that; we are all one color now."

Delaney, while an early nationalist or "race man," had by 1871 established a profitable land and brokerage business. He lectured on the harmony of interests between capital and labor, and denounced carpetbaggers as "the lowest grade of northern society." In 1876 he was the most prominent African American political leader to endorse former confederate general Wade Hampton for governor of South Carolina.

Hampton's campaign is recognized with 20/20 hindsight as the opening wedge, the Trojan horse, for restoring unbridled white supremacy across and beyond the former confederate states. But at the time, Hampton pledged to strengthen the educational system (South Carolina had no public schools before Reconstruction), avoid "vindictive discrimination" and provide protection against mob violence. He published a series of promises "to the colored people of South Carolina." He may even have meant it, but if so, he was a useful tool to men who intended to employ a great deal of violence after his election.

If allowed a little more space and time, and most of all land, the emancipated population would have developed as small family farmers and business owners, without waiting for Booker T. Washington's belated "Atlanta Compromise." Richard Wright's response to General Oliver Otis Howard, "Tell them we are rising" would have been the order of the day.

The impoverished "white" population of the states that made up the short-lived confederacy were "more radical against rebels than in favor of negroes" as one southern Republican leader said, but some were in favor of a redistribution of planter land. This would have fulfilled the basic substance of General Sherman's temporary war measure granting forty acres and a mule. One Republican newspaper in North Carolina proclaimed that Unionists must choose "between salvation at the hands of the negro or destruction at the hand of the rebels."

Many of the yeoman farmers who had been militantly pro-Union wanted relief from debts that threatened to cost them their farms, cattle, horses, mules, and independent existence. The national Republican party, on the other hand, envisioned massive opportunity for capital investment, requiring a compliant labor force and sanctity of private property and debts.

Freed people sought literacy, legal recognition of their marriages and families, religious liberty, and, the means to support themselves, a home of their own, land. One northern observer noted a sense "that they have a sort of right to live upon their own plantations." A young man directly told a visiting writer "My master has had me ever since I was seven years old and never gave me nothing." Accordingly, "I worked for him twelve years, and I think something is due me."

The New York Anglo-African editorialized:

What course could be clearer, what course more politic, what course will so immediately restore the equilibrium of commerce, what course will be so just, so humane, so thoroughly conducive to the public and the national advancement, as that government should immediately bestow these lands upon those freed men who know best how to cultivate them, and will joyfully bring their brawny arms, their willing hearts, and their skilled hands to the glorious labor of cultivating as their own, the lands which they have bought and paid for by their sweat and blood."

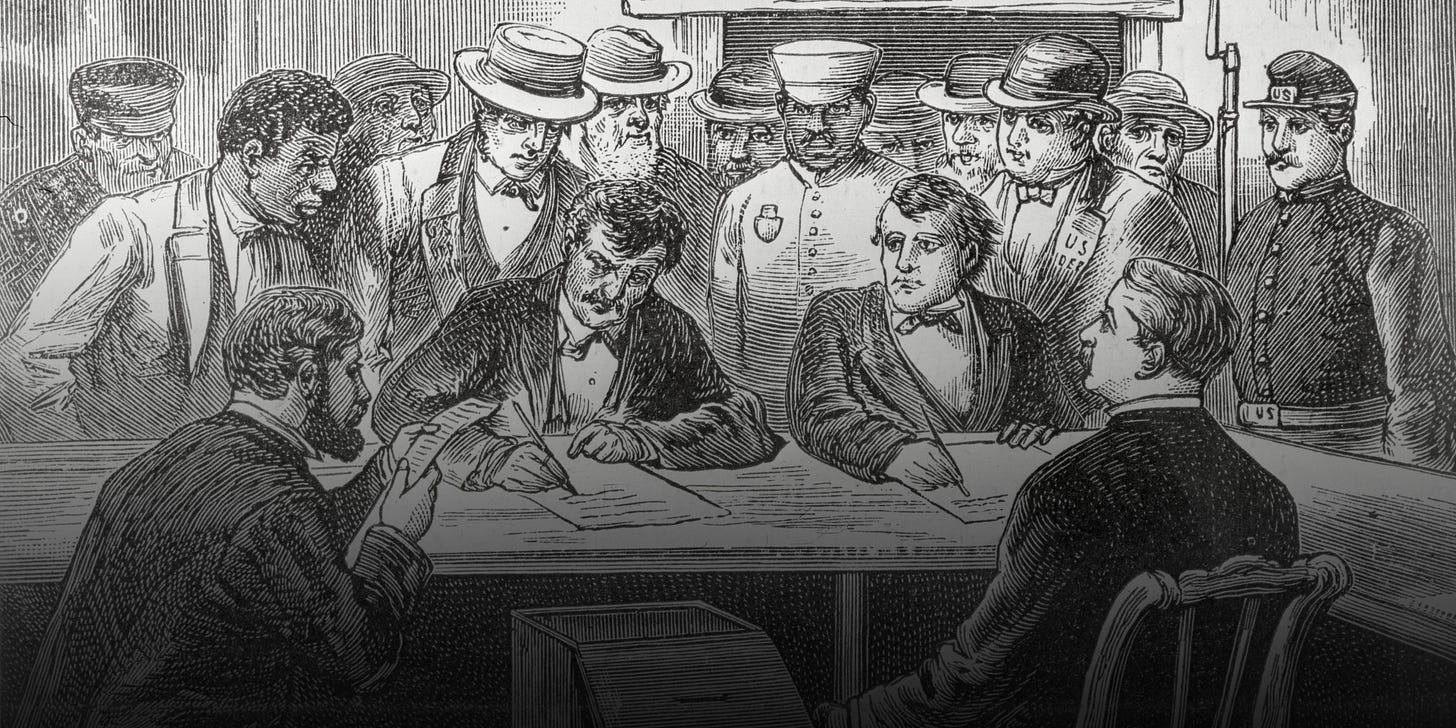

It was a common assumption in many political theories that a person was not truly free if they depended upon another for their livelihood -- whether as a wage laborer or a serf or a slave. On the elite side, this sustained an argument that only those who owned property could be trusted with the rights of citizens, particularly the right to vote. On the other hand, freed people feared that formal legal freedom would mean little or nothing if they did not attain self-sufficient ownership of their own lands or businesses. Indeed, failure to achieve this set the stage for the emergence of virulent Jim Crow rule at the end of the century.

A lot of impoverished "white" southerners had similar aims. They had been pushed onto the poorest and least productive soil while the masters of large plantations taught slaves to call them "poor white trash." Agrarianism, the demand for redistribution of land ownership, continued to be a popular cry for the next 30 years.

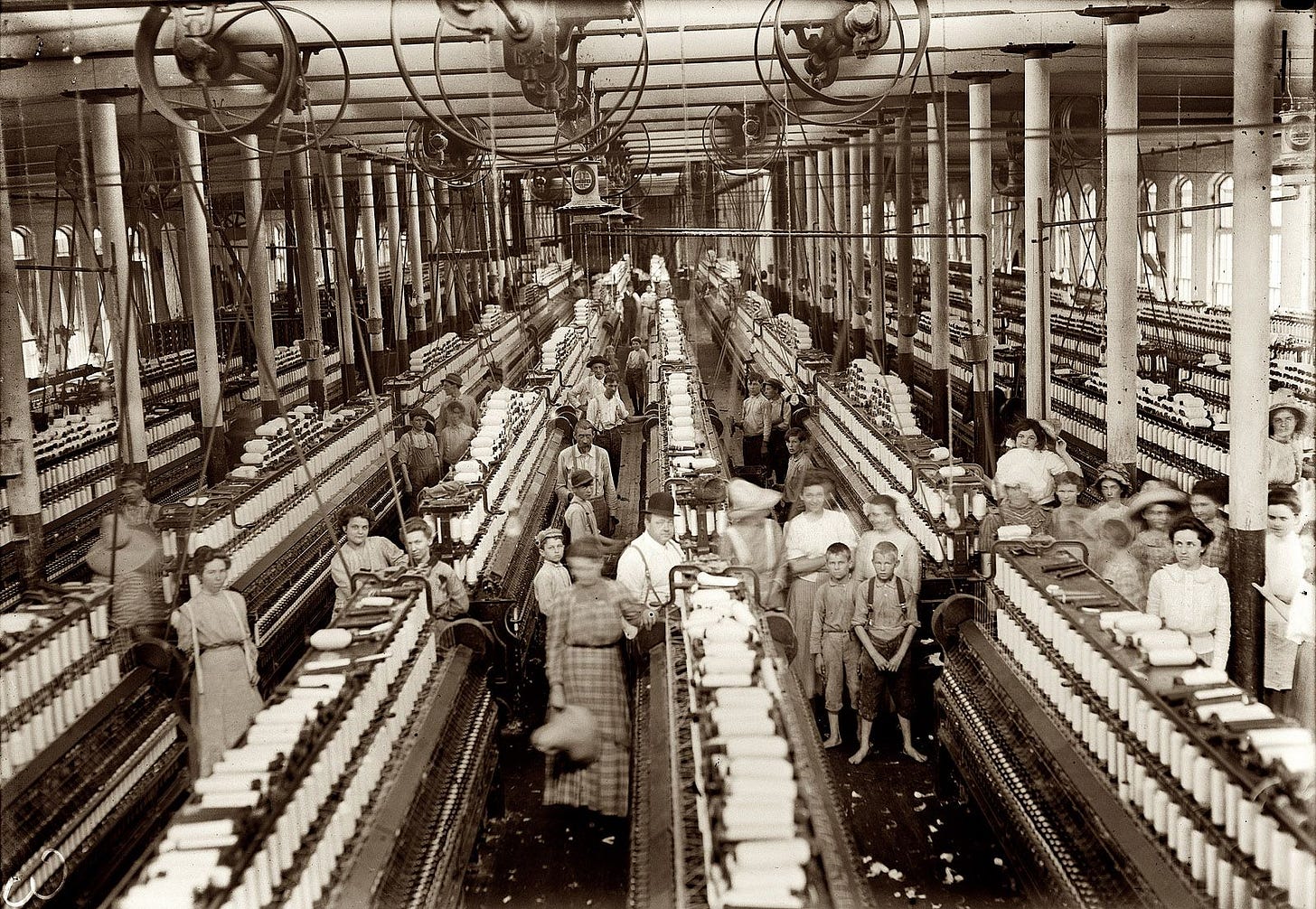

But the northern investors who held a good deal of power in the Republican Party wanted a good climate for investment. They wanted a disciplined wage labor force, north and south, subservient to large combines of capital. They wanted production of cotton to resume as soon as possible, to supply northern mills -- plus exports to England and France would help pay down the national debt incurred to fight the war. The Democratic Party sought to reclaim votes by denouncing "niggerism." Their 1868 campaign slogan was "This is a white man's country -- let white men rule." Between the two parties, virtually every aspiration of the newly freed population was quashed, and thrown back on racial identity for sheer self-preservation. Of course all the New England cotton mills moved south seeking cheaper labor.

For the facts presented here I have primarily relied upon Eric Foner’s A Short History of Reconstruction and Bruce Levine’s The Fall of the House of Dixie.