No, the Equal Rights Amendment is not part of our federal Constitution

We need to go back to the drawing board about discrimination on the basis of sex

I have a certain limited affection for Joe Biden's sincere and evident desire to Do The Right Thing, tempered by something bordering on contempt for his utter cluelessness in figuring out what that might be. His absolutely irrelevant parting statement, that the Equal Rights Amendment is now part of the Constitution of the United States of America, is one of many examples. Presidents have literally no role in approving constitutional amendments.

For millions in their young adult years today, the submission of an Equal Rights Amendment by congress to the states for ratification is ancient history. Two thirds of both houses of congress approved the amendment in 1972. That was twenty-five years before my nephew was born. My sister, his mother, was not yet old enough to vote. I voted for the first time that year — and only because the voting age had just been lowered to 18, by constitutional amendment. My nephew is now a married father of three. When I was born, World War II was more recent for me than the ERA is for my nephew's generation.

To stretch out the ratification of any constitutional amendment over that period of time, with all the shifting sands of politics and the rise and fall of ideological factions over nearly fifty years, is ludicrous. This is a Constitution we are talking about! This is the bedrock of our political and legal arrangements, the framework that by and large does not change, and is very difficult to change, unlike statutes which can be changed in the space of one election due to a shift in public opinion. To make fatuous declarations of ratification belittles the very nature of a Constitution!

But, actual disposition depends on legal technicalities. Congress provided that the amendment must be ratified by the states within seven years to be effective, extended by another three years in 1979 to 1982. To consider the amendment ratified requires setting that limit aside, on the ground that congress had no authority to set a time limit. That's dubious -- and especially dubious for something so profound as amending a constitution. But if congress had no authority to set a time limit, then the very resolution submitting such an amendment for state ratification was invalid. Congress would have to do its resolution all over again to get it right. Its like an illegal move in chess -- you have to take it back, and make a different move.

The XVIII, XX, XXI, and XXII amendments have specific language imposing the same seven year limit on ratification, and nobody challenged that language. Of course those amendments were ratified within seven years.

Then there is the debate over whether a state can rescind its ratification of a constitutional amendment. This, my dear fellow citizens, is why congress put a time limit on ratification. Over fifty years, the political disposition in many states shifted enormously. Virginia in 1977 was not at all disposed to ratify such an amendment. But its politics had shifted enormously by 2020, when the legislature did ratify the amendment. Meantime, the politics of Nebraska, Tennessee, Idaho, Kentucky, South Dakota and North Dakota shifted also. Remember when Al Gore was the pro-life Democrat representing a Tennessee district in congress? North Dakota used to be the political base of a kind of home grown Great Plains socialism.

Sarah Palin, who in her own bombastic way is as clueless as Joe Biden, used to shout that "the real Virginia" still supported her brand of politics, even though a majority of Virginia voters did not. But consider that many of those who now vote in Virginia and California and other formerly conservative states, perhaps used to live in Idaho, when it elected Frank Church to the United States senate. (Idaho turned more conservative when the copper mines closed, and a unionized workforce was dispersed to the four winds to seek a living from another source.)

Perhaps states cannot rescind ratification -- Professor Laurence Tribe from Harvard Law School cites a very real precedent where certain readdmitted southern states tried to rescind ratification of the 14th amendment. But all the more reason for a seven year limit -- so that the nation as a whole is making a coherent and sustainable decision within a relatively limited period of time.

Amending a constitution with integrity, so that it can be sustained and consistently enforced, requires an overwhelming supermajority of actual support and respect, not the kind of just barely made it over the finish line gasping for breath that has characterized our last three presidential elections. It is of course almost impossible to envision the ERA being accepted as an amendment by the courts or the office of the National Archivist in the forseeable future. So anyone who wants to accomplish anything along the lines of an ERA needs to think about petitioning congress for a new amendment to be submitted to the states. (Ruth Bader Ginsburg said as much shortly before she died).

I submit that a new ERA should be very different, somewhat longer, and more carefully considered than the last one. My mother never allowed her sex to be an obstacle to anything she wanted to accomplish in life. She was strong, outspoken, polished, erudite, intelligent and possessed degrees in math, chemistry and engineering. She spent some years staying home to raise young children and keep the house, but even when my sister was two years old, mom took on part time teaching at a local university extension. She was a member of the League of Women Voters and a reliable volunteer for the local Republican Party. I think an amendment that protects the right of any woman to live as she did and make independent choices would be valuable.

But the fact is, there are SOME REAL DIFFERENCES between men and women. A single sentence like the late ERA proposal, in the hands of any number of sharp lawyers representing any number self-interested clients could be badly mis-used. As a constitutional article, it would be very difficult to adjust. The law of unexpected consequences is very real. That is one, albeit only one of many, reasons why the ERA was met with considerable skepticism.

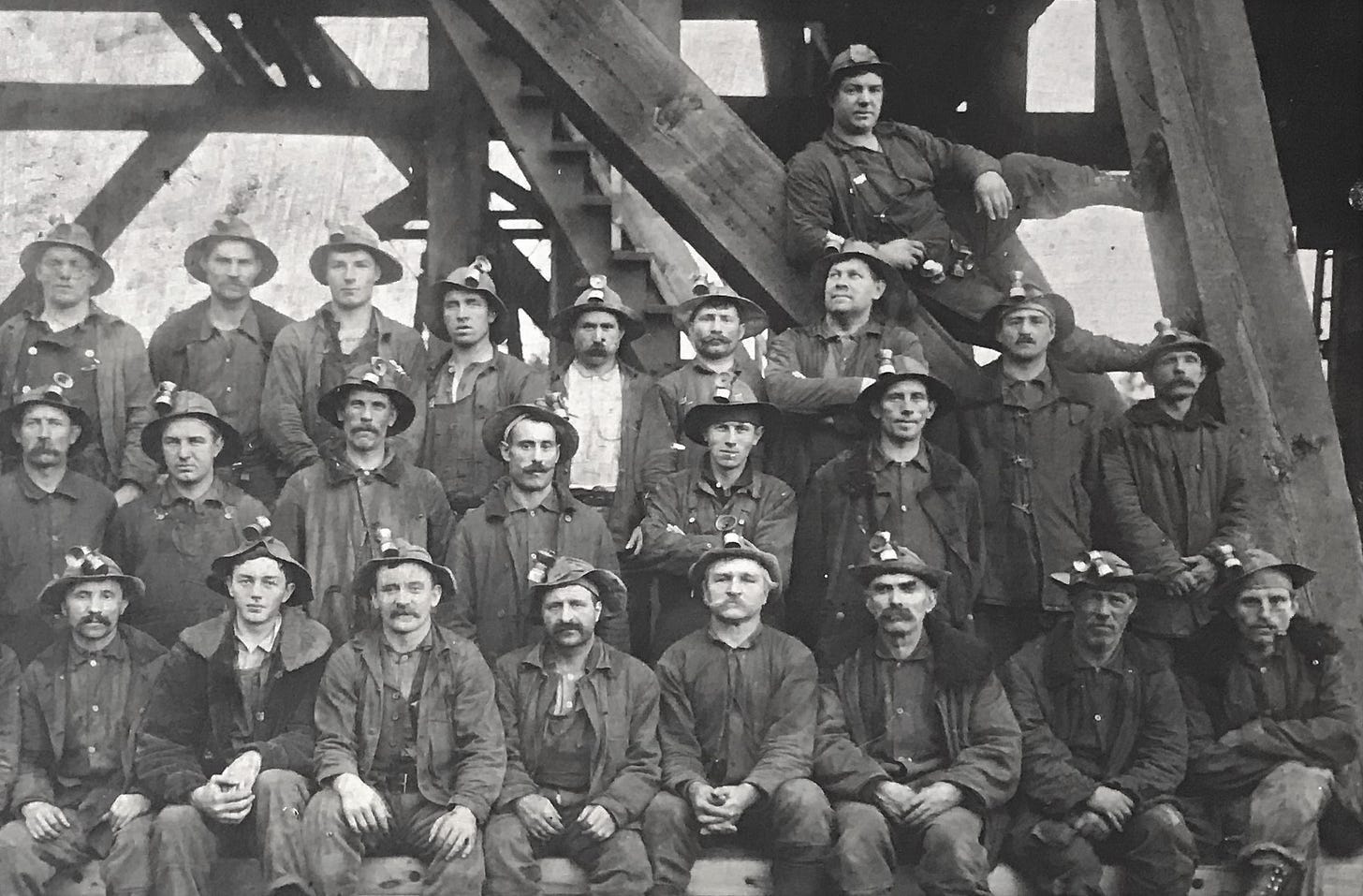

I have some history with the labor movement. Many labor protection laws have different standards for men and women. That is because in general, the mode and median height, weight, distribution of muscle mass, and skeletal structure of men and women are distinct and different. If the late ERA draft had been ratified, one of the first results would be employers in agriculture, mining, and heavy industry requiring female employees to lift the same weight as male employees, because "we can't discriminate on the basis of sex anymore." You know, like a 5' 2" woman being required to lift a 40 pound box of produce over her head into a truck.

Sure, employers could lower the requirements for men, but we know employers are by and large not going to do that. An ERA that only benefits privileged women with white collar and upper level professional careers is unworthy of being enshrined in our Constitution.

Then there are other physical differences. When pregnancy leave was first being proposed and occasionally implemented, there was blowback from "men's liberation" commentators who whined that it was unfair for women to get pregnancy leave, but not men. At the time, I suggested, OK, write the law to say any man or woman who becomes pregnant can get leave. Today, there are those who insist that "some men can become pregnant," which is of course nonsense. But an Equal Rights Amendment which fails to recognize that women have biological functions men do not would be a catastrophe. There is a place for men to have leave, either to support a wife who is pregnant, or to help with initial work of raising a newborn baby. But those are not identical functions, and the leave need not be identical in length or character.

Some women have advocated that public restrooms for women should be larger and have more stalls than for men, because about half the time women require more time. Its true that women's restrooms often have lines stretching out the door, while men's seldom do. But the bald language of the present ERA would sustain lawsuits about the "discrimination" of providing any differences in facilities at all. Then there is the possibility of lawsuits insisting that keeping separate facilities for women and men is itself discrimination on the basis of sex.

The differences between men and women are not nearly so great as many philosophers, politicians, and other once supposed. The notion that women are constitutionally unfit for voting, legislating, serving in executive cabinets, are functioning as professionals, such as doctors, lawyers, CEO's etc. has long since been discredited. There are women who claim that there are significant differences between the male and female brain, which is a dangerous road to travel down, but the distinctions are none to specific.

But the real differences must be recognized in any broadly written constitutional amendment. A section 2, section 3, section 4, to clarify intent is absolutely essential. E.g., Section 1: Distinctions in requirements for performance of physical labor by male as distinct from female employees shall not be erased by this article.

Section 2: Private facilities suitable for the biological functions of each sex need not be identical in scope under this article.

Etc. Etc. Etc. This will take some thought, some hard work, some sincere debate and conversation. Nobody should rush to pass another ERA without it.