Movies Lie, Part I: The movie Hidden Figures wasn't as good as the book

What the story -- video or volume -- still has to offer us

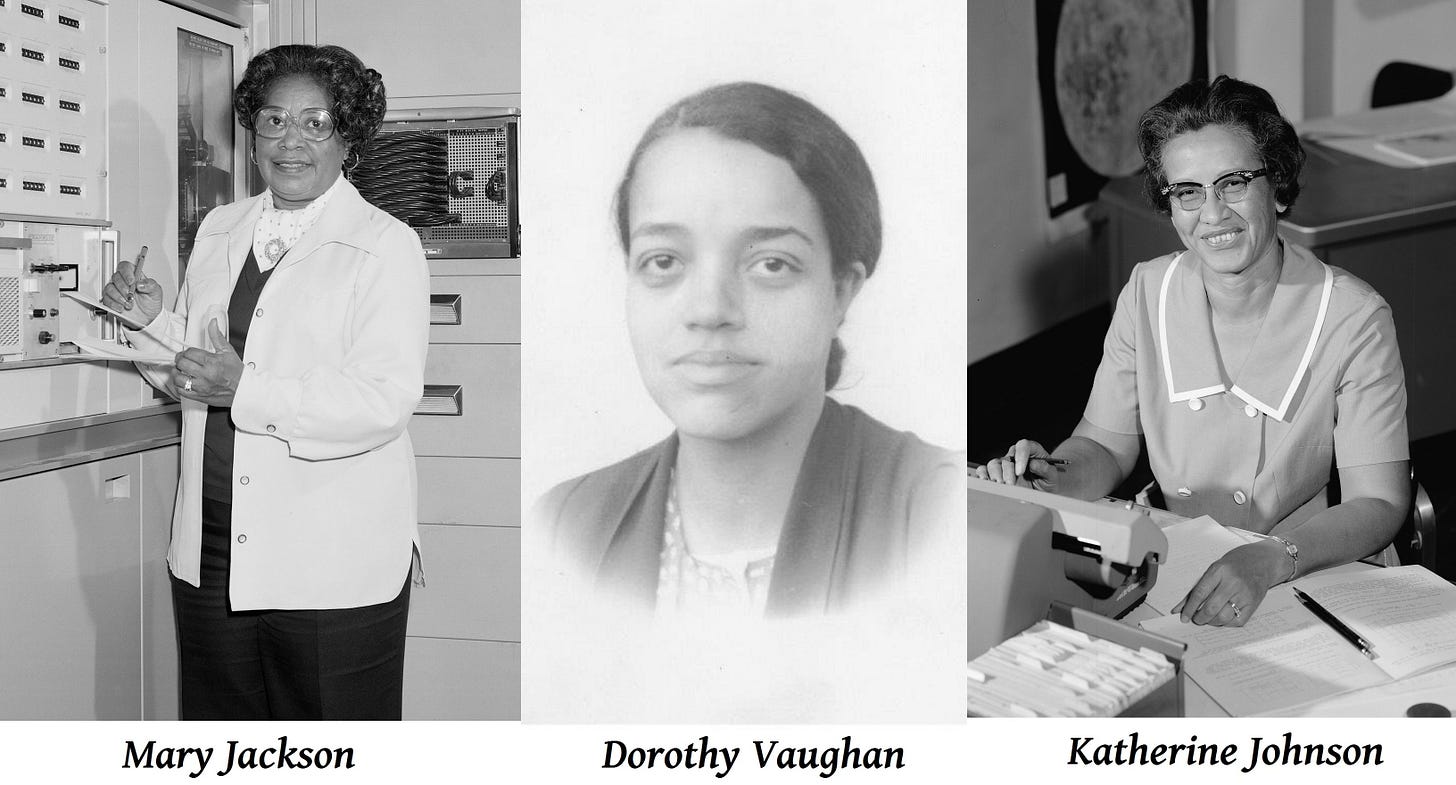

Its such heart-warming synergy in the movie Hidden Figures, when a Jewish engineer whose parents died in a Nazi extermination camp encourages Mary Jackson to pursue a career in engineering. In the movie script, Jackson says "I'm a Negro woman" and she's not going to expect the impossible. In fact, reading Margot Shetterly's book, Hidden Figures, Jackson was never reticent about pursuing her dream, and the colleague who encouraged her was Kazimierz Czarnecki, an ethnically Polish Roman Catholic born in New Bedford, Massachusetts, who had been working at the laboratory since 1939.

I loved the movie Hidden Figures when I first saw it at a movie theater. After watching it with me, Renee ducked into the ladies room and overheard some high school students talking about how they were going to pay more attention to their math classes. That's one of the best effects. I bought the DVD, and I've watched it several times. But I can't help thinking that putting the whole truth on the table would have a better effect than twisting things around to write an engaging script.

By the way, Mary Jackson didn't get surprised by an assignment from the computing group in 1961 to work with Czarnecki on the wind tunnel testing space capsules -- she vented at length to him in 1953 about some difficulties finding the "colored ladies" bathroom, and other racial boundaries, and he immediately told her, in person, "Why don't you come work for me?" -- an offer she immediately accepted.

That's right, it wasn't Karen Goble in 1961 at the National Aeronautical and Space Administration, who was told by a secretary (in the office where whe was assigned to calculate rocket trajectories), "I have no idea where your bathroom is." It was Mary Jackson in 1953, two years after starting work at the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics, who asked a few pale "white" employees where the bathroom was. They giggled, asking how they would know where her bathroom was. As Shetterly wrote, "It was the proximity to professional equality that gave the slight such a surprising and enduring sting." There were "colored" bathrooms somewhere in the east wing. She didn't have to run to the west wing -- but it was hunting through a maze to find them.

By many reports, that kind of thing didn't actually happen at NASA, but it happened a lot at NACA -- an agency founded by Woodrow Wilson. (Wilson was a Democrat, a Liberal, a Progressive, and an unapologetic racist, who refused admission of Paul Robeson's older brother at Princeton, and segregated the federal civil service, which had been integrated since 1865). By the time NASA was formed in 1958, federal agencies had grown a bit of a spine, the mission had a higher profile. Even if located in Virginia, NASA didn't strictly follow state "customs" in matters of race. But the ladies featured in Hidden Figures had worked for years at NACA in the 1940s and 1950s, and the humiliating experiences there were very real.

The West Computing Group was actually dissolved when NACA and several other agencies were merged into NASA, not after John Glenn's orbital flight. By the time it was officially dissolved, most of the computers (the live black woman doing advanced math -- not the machines) had already transferred to a variety of other departments. The last segregated work unit was over. That was the conclusion of Dorothy Vaughan's time as a supervisor, not the beginning. They didn't all move en masse to program the IBM computer. But Vaughan did master Fortran, and start a second career translating engineers' equations into the programming language. She retired in 1991, after hoping for a promotion that would return her to management, which she didn't get. By the way, Dorothy Vaughan never learned to drive.

But, to entirely contradict my own criticism, I still love the movie episodes when she tiptoes into the computer room, fixes the misplaced wires, and gets it going. Its just so much fun, even though that kind of drama only happens in fiction. In the real world, things start happening before the historical date everyone recognizes, and keep developing in new ways long after.

Movies have to compress several weeks, months, years, into a couple of hours of engaging entertainment. So all sympathy to the script writer who has to hold an audience's attention, inspire an audience to want to come see the movie, highlight the highs and lows of real life experience, squeeze it all into an alloted time, and now I'm asking why they didn't keep it all precisely accurate. But sometimes, we get lost in the movie script and we still don't know the history we are trying to come to terms with.

One of the worst scenes was Mary Jackson's appearance in a state courtroom to seek an order admitting her to engineering courses held at Hampton High School, an "all-white" institution. (Hampton High School served in the evening as a University of Virginia campus, mostly serving NACA employees at Langley.) I was skeptical the first time I saw that scene. First, its unlikely a judge would have put on the record that "no matter what the Supreme Court says" Virginia was still "a segregated state." Southern segregationist judges were more subtle and devious about their choice of wording, with an eye on appellate review by federal courts. Second, there is no way she got a court order by doing research on the judge's personal history and warming the cockles of his heart.

I found that the scriptwriters had said publicly that they didn't know what happened in that courtroom, so "We had to use our imagination." They did a poor job of it. First, if they had rummaged around in the basement storage of the court house, they might have found a transcript. Second, if they had studied the state of civil rights jurisprudence at the time, they might have found Donald Gaines Murray's case seeking entry to the University of Maryland law school in 1935, about twenty years earlier.

The ultimate ruling from Maryland's highest court is that the "separate but equal" doctrine developed in Plessy v. Ferguson, which was still binding law at the time, required the state to provide a law school of identical size and architecture, with an identical library, and an equally distinguished faculty, for "colored" law students ... or admit Murray without restrictions to the law school it already had. The university trustees begged the legislature to fund such a school so they wouldn't have to admit Murray to the "white" law school; the legislature wasn't about to do that.

But, again simply looking in Shetterly's well-researched book, there was no court case. Mrs. Jackson was required to petition the City of Hampton for "special permission" to attend the segregated school -- which was granted, although having to appear and make a case that this Negro woman should be allowed to take the engineering courses was a humiliation to be endured. That was in 1956, not in the early 1960s. The fact that courses were mainly for NACA employees at Langley, probably carried the day. Its worth noting that most engineering schools across the country denied admission to any woman, no matter what her race, creed, color or national origin, at that time.

It might also have been salutary if the movie had covered Jackson's surprise to find what a "dilapidated musty old building" the school was. "She had just assumed that if whites had worked so hard to deny her admission to the school, it must have been a wonderland," Shetterly wrote. It wasn't. Jackson realized that it cost a lot of extra money to keep two racially segregated school systems, and the money could be better spent building a clean, modern, well-equipped school for children of all races.

It is true that John Glenn said "get the girl to check the numbers" before his orbital flight, and Karen Johnson did. She actually got the assignment by phone, not by one of the engineers assigned in an emergency to be a special courier.

How could all this have been kept in better and more comprehensive perspective? Perhaps the work the ladies actually did at NASA could have been shown more accurately, with flashbacks to all they had endured at NACA. In that framework, how NASA still fell short could have been presented as well. Perhaps the presence of both men and women, and a mix of complexions, in a variety of departments, could have been presented, while still focusing on three ladies whose careers were certainly significant.

Shetterly notes that Katherine Johnson "is often mistakenly reported as having been sent to the 'all-male' Flight Research Division" when that division "included four other female mathematicians, one of whom was also black." The movie sometimes followed the common misconceptions, rather than the book on which the script was loosely based.