Gandhi, 77 years after he died, 45 years after the movie swept the world

Has the world really changed? have empires really paused?

When the epic movie, Gandhi, was made in 1980, the Indian National Congress Party had held power almost uninterrupted from 1947, and would continue, with one brief interruption, through 1989. The movie was a triumph, sought by India's first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, since at least 1962. There were some, including future prime minister Morarji Desai, who denounced the very idea of making a movie about Gandhi. Although a Hindu, Desai seemed to view this in a similar way to Muslims insisting that no movie or artistic depiction should ever be made of Muhammad.

Watching the movie again in 2025, marking eleven years of uninterrupted domination by the Bharatiya Janata party, it is easy to wonder wether Gandhi's dream of a unified India is a complete failure. Almost nothing has turned out the way he envisioned it. Those who assassinated Gandhi were pleased to see their dream of Hindu nationalism and domination empowered under the reign of Narendra Modi. Both sought to validate Hindu culture as the dominant national culture, when necessary subordinating the concerns of India's Muslim, or even Buddhist and Christian minorities. Traditional Hindu culture has some very dark sides.

Gandhi himself never held public office. He was arguably more effective that way at mobilizing masses of people. It could also be argued that he never held real responsibility for delivering results, once independence had placed power in the hands of those who had long demanded it. Gandhi was a genius at resistance, and demanding independence, but a successful independence movement has to form an effective government, and try to please the diverse populations that for one reason or another turned out to make victory possible. Gandhi doesn't seem to have thought much about effective government.

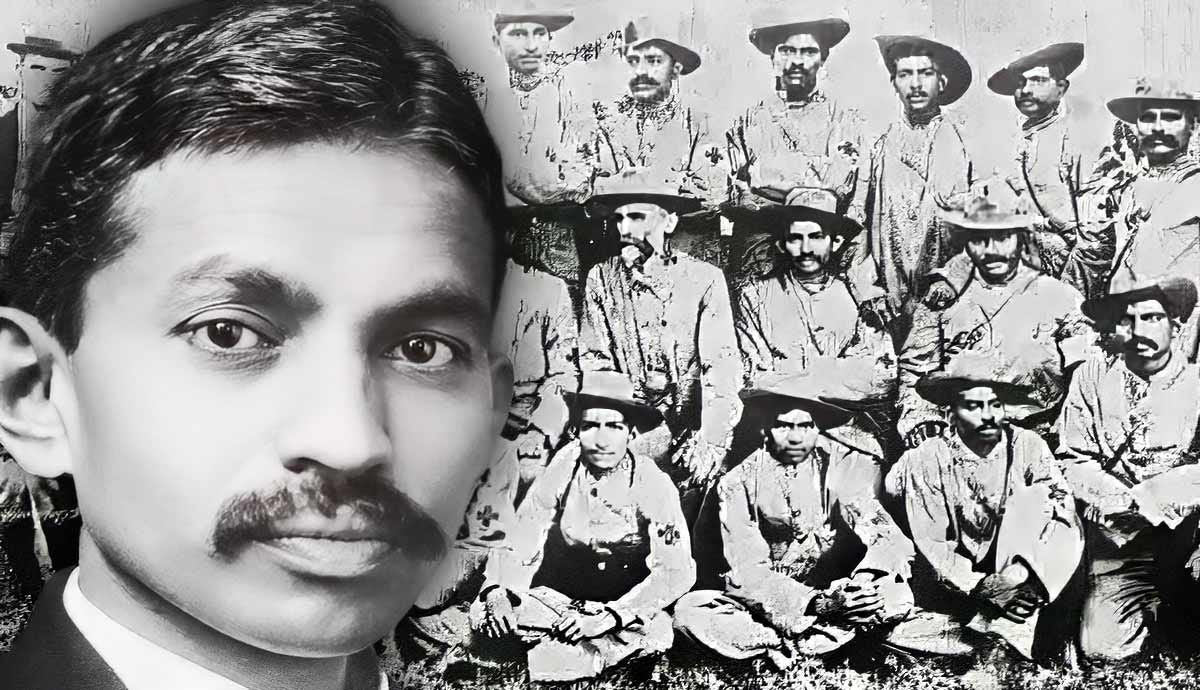

Early in his adult life, Gandhi was a dapper, well-dressed lawyer. His earliest protest movement, in South Africa, demanded the rights of Hindu, Muslim and Sikh immigrants as citizens of the British Empire. After returning to India, he increasingly sought separation from the Empire. At one point when a legal claim seemed promising, he said to his wife "I told you about British law." She replied with a laugh, "And I told you about British policemen."

His transition to wearing minimal traditional cotton clothing was not so much a commitment to becoming an ascetic. It served perhaps the most important point he made on returning to India from South Africa: India is not a congress of lawyers in a few cities. "India is 700,000 villages." He added that substituting native Indians for British civil servants and lords would do nothing for the people, if the same laws and economic relationships prevailed.

In fact, many theories of anti-colonialism and neo-imperialism have been turned on their head by the early 21st century. The Indian masses may remain mired in poverty and primitive social codes, but Indian billionaires control corporations that have bought up iconic British brands, including steel and automobiles. The global elites that control international capitalist finance and investment are more diverse, but they remain structurally the same.

If he understood nothing else, Gandhi recognized that if you don't transform life at the level of each and every one of those villages, you haven't changed much at all. That can't be done by issuing edicts and manifestos, and it cannot be done by simple coercion. This is a fact that has plagued many liberation and independence movements.

The leaders of many independence movements in Africa were university-trained intellectuals, often Oxford and Cambridge graduates. Their heads were full of great ideas, but their grasp didn't reach down to the level where most people lived their lives. Also, the colonial period had not left much in the way of comprehensive institutions. There were traditional tribal and ethnic loyalties. There were ancient national identities and former monarchies. There was a bit of a civil service. And there was the institution colonial authorities had done the most to build: the army. In the end, the army often took control.

For all his insight into what it meant to truly transform a country, to build a nation, Gandhi too failed to grasp the depth of malign traditions and ancient prejudices. The leaders of the independence movement were, for the most part, Hindu Brahmins, members of the highest and most prestigious of the four traditional varna of Hindu culture. (The varna are often called castes -- a rather imprecise Eurocentric translation first developed by Portuguese explorers). The Brahmins who sought independence were educated men with benevolent and enlightened intentions, but that didn't transfer very far downward. The leadership also included a number of wealthy, educated, sophisticated Muslim gentlemen.

At the regional, local, and village level among Hindus are thousands of jati -- which are also imprecisely translated as castes. Some years ago, a story made it into the western daily news of a village with two jati -- one dominant, the other submissive. A young lady who was born into the upper jati had fallen in love with a young man from the despised jati. Her extended family hung both of them from a tree, while guarding all roads with automatic weapons to make sure nobody took word to the police in time to prevent it. Gandhi would not have approved. But Gandhi was never able to drain the swamp of traditional culture out of those 700,000 villages.

Many of the optimistic hopes for an independent India foundered on division between Muslims and Hindus. The dominant Vedic culture had developed in India around 1500 BC. There are historians who deny any kind of invasion, but traces of this culture can be found earlier in what is now Syria. There are many ethnic and national groupings within India, which undoubtedly arrived and settled at different times, but the dominant Hindu culture arrived with one set of invaders, and, about 2500 years later, so did Muslim culture and faith.

Islam arrived partly with invading conquerors, but many born into less prestigious varna, or who were avarna, or some particularly despised jati, sought conversion to Islam as an escape from that status. Later, some became Christian converts for the same reason. On the other hand, Pakistan is rife with various clannish groups loosely termed “castes” jostling each other. By the time the independence movement got underway in the early 20th century, Muslim and Hindu populations were intermixed all over India, with Muslim majorities in the northwest and the far east of the country.

Initially, the demand for independence united both Hindu and Muslim voices, with one of the most prominent leaders being a nominal Muslim, Muhammad Ali Jinnah. He was a wealthy man of an established family who enjoyed fine wine and other alcoholic beverages -- to him the Muslim population was more a demographic and political body than devout practitioners of a faith or doctrine. But faced with the prospect of actual independence, forming a government without British supervision, unity broke down in mutual fear and distrust. The British had long used these divisions to justify British rule, but the independence movement had not erased them.

Jinnah turned from "India demands home rule" to a demand for partition of the British dominion known as India into two nations, one Hindu, one Muslim. If he also meant to insure that he was the leader of at least one, diminished, nation, he died soon after, and, the military took control of Pakistan for most of its subsequent history. The artificiality of trying to make a new nation called Pakistan out of two very different sets of people sharing only a common religion also failed, as East Pakistan became Bangla Desh. Both separations came at a cost of several million lives.

About 172 million Muslims remain in India, while 250 million live in Pakistan and 170 million in Bangladesh. Almost all Hindus living in Pakistan had to leave, and many Muslims migrated the other way, while riots killed several hundred thousand to two million people, and 12 to 20 million were displaced. Whatever the merits of Gandhi's satyagraha, the creative non-violence emulated by Martin Luther King, Jr., the results fell far short of his vision.

To film Gandhi's funeral for the movie, 400,000 people turned out to be the mourning crowd -- unpaid, as if it were an actual replay of the funeral, which it nearly was. I wonder whether anywhere near that many would turn out today. American General George C. Marshall was quoted as saying that Gandhi made "humility and simple truth more powerful than empires." But I wonder which empire that might be. Advertising for the movie proclaimed "His triumph changed the world forever." But I wonder, looking around the world now, if it really changed the world much at all.

Certainly he challenged the British Empire. But an American professor born in India once told me, the British Labor Party was committed to Indian independence since 1928. Once Winston Churchill was turned out of office in the elections of 1945, it was a done deal. Without men like Gandhi, independence and ending colonialism might not have even been an issue. But what came next was almost always a profound surprise, and not always a welcome one.