Compulsory vaccination: 1905 Supreme Court ruling on public health mandates

Jacobson v. Massachusetts ruled 7-2 there is no constitutional violation

On 20 February 1905, exactly 120 years ago, the United States Supreme Court issued its ruling in Jacobson v. Massachusetts, (197 US 11). The primary holding was:

A state may enact a compulsory vaccination law, since the legislature has the discretion to decide whether vaccination is the best way to prevent smallpox and protect public health. The legislature may exempt children from the law without violating the equal protection rights of adults if the law applies equally among adults.

A Massachusetts law provided that the board of health of a city or town may require and enforce vaccination and revaccination of its inhabitants, while providing them with a way to get free vaccinations. The state imposed a $5 fine for people over 21 who violated this law, although it provided an exception for children with a doctor's certificate stating that they are not fit for vaccination.

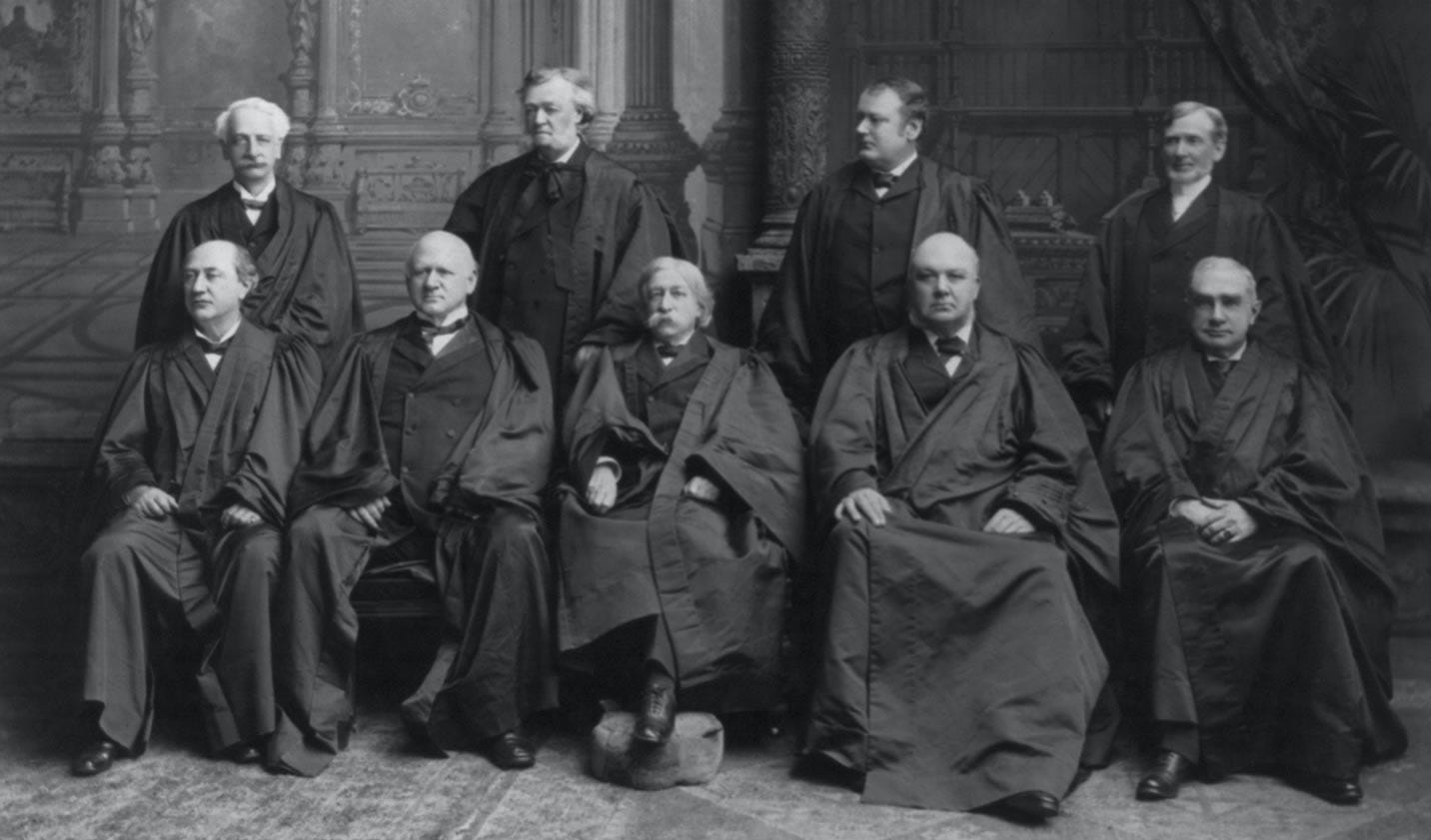

The seven justices in the majority were:

John Marshall Harlan (Author)

Melville Weston Fuller

Henry Billings Brown

Edward Douglass White

Joseph McKenna

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

William Rufus Day

Justices Brewer and Peckham dissented.

Harlan ruled that the vaccination law did not violate the 14th Amendment because the police power of the state may be allowed to constrain individual liberties through reasonable regulations when required to protect public safety. He reasoned that individual liberty does not allow people to take actions regardless of the harm that they could cause to others. Harlan wrote that the plaintiff had failed to show that the vaccination law was arbitrary or oppressive, or not reasonably required for the safety of the public.

Harlan noted the increasing presence of smallpox, which prevented the plaintiff from convincingly asserting that the rule had no real or substantial relation to protecting public health and safety. Although the plaintiff presented evidence that some doctors believed that the smallpox vaccine was not effective and could cause further diseases, Harlan pointed out that the opposite view represents the common medical belief and is followed by more reputable doctors. Although he largely deferred to the legislature, Harlan noted that requiring a vaccination for certain people with certain health conditions would be cruel and inhumane. This would justify a court in shielding them from the enforcement of the law.

This has been the ruling precedent in constitutional jurisprudence ever since. No, requiring vaccinations to protect public health generally does not violate anyone's constitutional rights. In certain specific circumstances, such a requirement could be cruel and inhumane, and laws should provide for such exceptions.

The defendent, Jacobson, claimed that mandatory vaccination violated his rights under the Preamble of the Constitution. The court ruled that "The United States does not derive any of its substantive powers from the Preamble of the Constitution. It cannot exert any power to secure the declared objects of the Constitution unless, apart from the Preamble, such power be found in, or can properly be implied from, some express delegation in the instrument." The Preamble, "We the People of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union..." sets forth the purposes of writing a constitution, but does not delegate or restrain specific exercise of government powers.

Jacobson claimed a violation of the "spirit of the Constitution." Justice Harlan, writing the opinion of the court, cited former Chief Justice John Marshall that "the spirit of an instrument, especially of a constitution, is to be respected not less than its letter, yet the spirit is to be collected chiefly from its words."

Ruling earlier on the same case, the Supreme Court of Massachusetts observed that Jacobson's claims "involved matters depending upon his personal opinion, which could not be taken as correct, or given effect, merely because he made it a ground of refusal to comply with the requirement. Moreover, his views could not affect the validity of the statute, nor entitle him to be excepted from its provisions."

Harlan also wrote that "for nearly a century, most of the members of the medical profession have regarded vaccination, repeated after intervals, as a preventive of smallpox; that, while they have recognized the possibility of injury to an individual from carelessness in the performance of it, or even, in a conceivable case, without carelessness, they generally have considered the risk of such an injury too small to be seriously weighed as against the benefits coming from the discreet and proper use of the preventive, and that not only the medical profession and the people generally have for a long time entertained these opinions, but legislatures and courts have acted upon them with general unanimity."

People lining up for mass distribution of long-awaited polio vaccine. After the initial vaccine developed by Jonas Salk, which was injected, Albert Sabine developed one that could be delivered in a sugar cube.

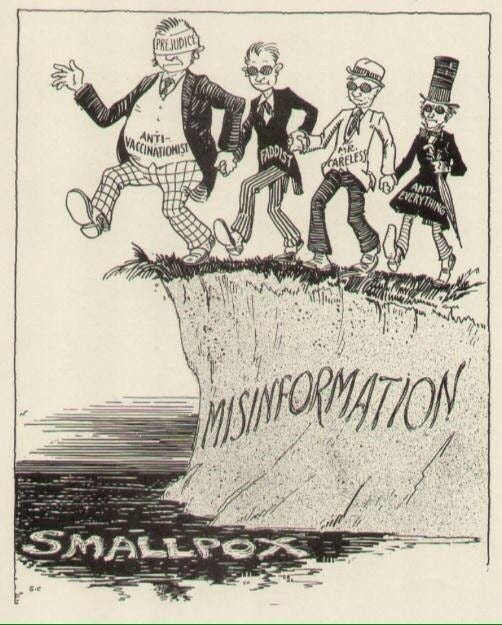

Refusing vaccination not only endangers the life and health of the individual who refuses. It also endangers the lives of everyone else in the community, either by allowing a pathogen to spread, or by providing a pool of vulnerable individuals among which the pathogen can mutate, even perhaps developing resistance to the vaccine that has protected everyone else. Smallpox vaccinations are no longer required in the 21st century, or generally even available, because thanks to vaccination, smallpox has been eliminated. Samples exist in deep freeze in two laboratories, nowhere else.

Harlan explained, "The authority of the State to enact this statute is to be referred to what is commonly called the police power -- a power which the State did not surrender when becoming a member of the Union under the Constitution. Although this court has refrained from any attempt to define the limits of that power, yet it has distinctly recognized the authority of a State to enact quarantine laws and 'health laws of every description;' indeed, all laws that relate to matters completely within its territory and which do not, by their necessary operation, affect the people of other States. According to settled principles, the police power of a State must be held to embrace, at least, such reasonable regulations established directly by legislative enactment as will protect the public health and the public safety.

"There is, of course, a sphere within which the individual may assert the supremacy of his own will and rightfully dispute the authority of any human government, especially of any free government existing under a written constitution, to interfere with the exercise of that will. But it is equally true that, in every well ordered society charged with the duty of conserving the safety of its members the rights of the individual in respect of his liberty may at times, under the pressure of great dangers, be subjected to such restraint, to be enforced by reasonable regulations, as the safety of the general public may demand. An American citizen, arriving at an American port on a vessel in which, during the voyage, there had been cases of yellow fever or Asiatic cholera, although apparently free from disease himself, may yet, in some circumstances, be held in quarantine against his will on board of such vessel or in a quarantine station until it be ascertained by inspection, conducted with due diligence, that the danger of the spread of the disease among the community at large has disappeared."

The state legislature proceeded upon the theory which recognized vaccination as at least an effective, if not the best, known way in which to meet and suppress the evils of a smallpox epidemic that imperiled an entire population.

Harlan also cited a recent case from the New York Court of Appeals. "One contention was that the statute and the regulation adopted in exercise of its provisions was inconsistent with the rights, privileges and liberties of the citizen. The contention was overruled, the court saying, among other things:

'Smallpox is known of all to be a dangerous and contagious disease. If vaccination strongly tends to prevent the transmission or spread of this disease, it logically follows that children may be refused admission to the public schools until they have been vaccinated'."

The Supreme Court was "not prepared to hold that a minority, residing or remaining in any city or town where smallpox is prevalent, and enjoying the general protection afforded by an organized local government, may thus defy the will of its constituted authorities, acting in good faith for all, under the legislative sanction of the State."

Those have remained the constitutional boundaries to mandatory vaccination as a public health measure. It does not infringe personal liberties protected by the constitution, but, there should be provision for exceptions in circumstances where vaccination may harm a particular individual for specific reasons. COVID-19 was not, of course so great a peril as smallpox and polio have been, but it did kill hundreds of thousands, and pack Intensive Care Units in hospitals all over the country to the point of overflowing. Thanks to decades of mandatory vaccination, smallpox, polio, measles, mumps, rubella, chicken pox, whooping cough, tetanus, diptheria, and other communicable diseases no longer claim thousands of lives a year. But some, like polio and measles, are still around and waiting for an opportunity to reinfect an unvaccinated population.