A Brief History of Communism, for those who have no frickin' idea what it means

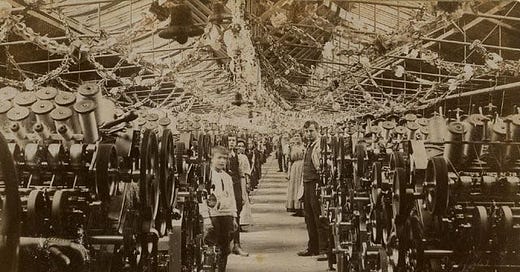

It all started with a lot of disgruntled weavers

Weaving was a respected skilled trade with well organized guilds in medieval Europe. It was one of the first skilled trades to be heavily industrialized. Goldsmithing was not a high priority for mechanization, and even shoe making came a little later. Weavers found themselves no longer "masters of their own time." They worked the hours they were told to, by distant magnates who now owned all the essential tools of their trade, and received whatever wage these early industrial investors chose to pay them. The weavers were angry.

Communism is a term that developed long before Karl Marx was born. The weavers, and some others feeling similar effects, wanted to take back control of what Marx would later call "the means of production." After all, they could remember a time when they owned their own tools. They noticed that although most governments were still royal, noble, feudal, somehow the government passed laws to smooth the way for mill owners. They were profitable, and the king could tax the mills and the commerce they generated. In England, the liberals made it even worse than the Tories. Liberals did not want the workers in their enterprises forming unions.

Often, some of the more "progressive" nobility invested in factories themselves. Upstart former peasants who became rich building mills sought titles for themselves, or offered to marry their daughters into proud but debt-ridden or destitute titled families. When Karl Marx later wrote about "community of women" and how the bourgeoisie delight in seducing each other's wives, he neglected to mention that both the nobility and the rising capitalists delighted in pimping their daughters to best dynastic and commercial advantage.

So, early unions, or simply informal mass meetings and conversations in taverns, began talking about how the wage workers could take control of the machinery that controlled their lives. To do that, they would have to take control of the state, the power that kept them helpless and denied them recourse. This was the beginning of communism.

Karl Marx was a student of a German philosopher, Georg Wilhelm Friederich Hegel. Many generations of Marxists considered this a gift that Marx brought to the working class movement. With 20/20 hindsight, it was probably a curse, not a blessing.

But Marx earnestly wanted to provide an intellectual and philosophical framework to help the destitute working class organize itself successfully to seize power -- as the weavers had sought to do. Hegel saw history as the result of a World Spirit working to fulfill and actualize itself. This lends itself just as well to the Kings of Prussia making themselves rulers of a German Empire, or to the scribblings of Adolf Hitler, as to anything else. But Marx saw an inevitable historical development, not of a self-actualizing spirit, but of a series of class struggles leading to an inevitable conclusion. Silly boy, nothing in history is inevitable.

Marx's theory of history was an inspiration of sorts, but it was an artificial overlay that didn't reflect reality on the ground. Still, in 1848, shortly after publication of the Communist Manifesto, there was a revolutionary upsurge all over Europe. Marx and his sidekick Frederick Engels didn't organize or even inspire this revolution, but, they tried to analyze, define, perhaps lead, and certainly applaud it.

Back around 1970, Scholastic Book Service published a pair of cold war propaganda pamphlets called "What You Need To Know About Communism -- And Why" and, its companion, "What You Need To Know About Democracy -- And Why." The funny thing is, both books talk about the revolutions of 1848. In one book, it is described as a great patriotic attempt to overthrow feudal autocracy and achieve democracy in Europe. In the other book, it is described as a nefarious conspiracy by Marx and his cohorts, a brutal violent destructive episode. Truth to tell, it was both and more.

Spontaneous uprisings aren't strategic. People don't act according to a plan. One mob does one thing, one another. People react emotionally rather than calculating how to establish a new order. Some want to tear down the palaces of the aristocracy in sheer fury, others want to turn out their lazy rich occupants and use the beautiful buildings for schools. Uprisings may spread from one nation to another, but in each nation goals and attitudes and methods are different. In the end, it was a real bust all around.

Those with the largest and most professional armies restored the order they wanted. Those with the budgets to pay an army and keep it in the field triumphed over those who left their homes for a day or a week to vent their anger at the established order. In France, Napoleon's nephew presided for twenty years over the Second Empire that supplanted the Second Republic. And he won an election on his way to claiming the imperial throne. In Germany the amalgam of ruthless industrialists and hereditary military nobility that would defeat France in 1870, nearly win the First World War, and then accept Adolf Hitler as the genius who would restore German greatness, settled in to proclaim "Deutschland Uber Alles."

England didn't have an uprising. Great Britain had a penal colony in Australia for those who might threaten one. England had already shot, hanged, deported, and generally crushed the Chartists, who made simple demands like, why shouldn't every adult vote. At least every adult male, and a lot of Chartists advocated that women should vote too. Queen Victoria thought that was absurd. A woman could reign, but women, plural, were not fit to vote. Karl Marx found a refuge in England where he could spend his days at the British Imperial Library, looking up unreliable statistics from the British civil service, and writing drafts of Das Kapital. The British didn't feel his presence to be a threat in the least.

The revolution crushed, all kinds of schools of thought emerged. Clearly, running out into the streets and building barricades out of paving stones was not the path to victory. Some timidly began running candidates for office in whatever parliament or national assembly might be available. Some despaired of the masses and turned to individual acts of violent terrorism. Anarchism emerged as a philosophy that instead of trying to take state power, it was better to simply destroy the state and not have one. Then everyone would truly be free, right? (Sure, until the next gang emerged to establish a protection racket.) A lot of intellectual schools of thought stepped out to attach themselves to the working class movement like barnacles on a wooden ship.

The word communism practically disappeared. Those who began to call themselves Marxists adopted the name Social-Democrat. Being a social-democrat could get a man fired from his job even faster than being a communist in the United States in 1950 could. When Louis Napoleon's empire collapsed in 1870, after defeat by the armies of the North German Confederation, spearheaded by Prussia, and joined by Bavaria and a few other states, a brief revolution emerged in Paris called La Commune de Paris. It was a mix of outraged patriotism and determined socialist revolution all mixed together.

The French imperial elite had capitulated to the German enemy. The people of Paris would not give up their beloved capital. The bourgeoisie seemed complacent about the surrender, and more afraid of the populace than of the national enemy. All the old revolutionaries who had been biding their time stepped forward. The German army released divisions of the French army to go take Paris from the revolutionary populace, so that the French army could surrender the city for the crowning of the German Kaiser. Naturally, after considerable resistance, the Commune de Paris collapsed.

In the ensuing decades, Lenin emerged from the cold wastes of Russian imperial autocracy. It must be understood that Lenin saw a gaggle of infatuated idiots very much resembling the post 1970s American and European "left." He wanted to clear the lot out of the way. They were amateurs, obsessed with nonsense, who couldn't organize their way out of a paper bag. He wanted a tightly disciplined professional outfit that could go toe to toe with the most ruthless secret police, build power with a clear eye, act strategically to strike when and only when victory could be achieved. Most of his criticisms and aspirations were correct. He asserted that a tightly disciplined party with an authoritative central committee could win where all else had failed. But what would it win?

He didn't use the word communist. He, like all revolutionaries of his time, were social-democrats. His faction were the Bolsheviks which can be translated "of the majority" or "maximilist." (They did have a majority at one illegal party congress in exile once, then they lost it.) He spent over ten years in exile in Switzerland. Alexander Solzhenitsyn wrote a rather good book about this period of Lenin's life, titled Lenin in Zurich. Then Lenin had several strokes of unexpected good luck. In the midst of a world war, the Russian state simply cracked. It couldn't sustain its army, inspire its army, discipline its army, pay its army, or maintain the loyalty of the civilian population, even locked in a massive war with Germany and Austria.

Lenin finagled his way back to Russia. He failed twice to lead an uprising against the Provisional government, that was trying to establish democracy and restore discipline in the army at the same time, to no avail. Finally, he found an opening and seized the government. After a three year civil war that knocked down what industrial plant Russia had, leaving the entire landscape that used to be the Russian empire numb and exhausted, he just barely came out on top. Then he denounced social-democracy, calling on people in every land to form new parties, for which he brought back the long-disused word, "communist."

He was popular around the world for a time. After all, he had done the one thing nobody else had ever succeeded at doing. He had won a revolution in the name of the working class, rather than going kicking and screaming into that good night of revolutionary failure. He also was the only voice calling for the colonized areas of Africa and Asia to be free -- so many of those seeking to free their countries from European, or in a few cases American, occupation decided they were communists too. Who else was speaking up for them?

There were of course some flies in the ointment. For twenty years or more, part, not all, of working class movements around the world were inspired by the example of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (Soviet means workers council, and it looked like the fulfillment of all the weavers had dreamed of centuries earlier.) After the USSR collapsed around 1990, there was a common joke in eastern Europe: "We knew they were lying to us about socialism, but unfortunately, they were telling us the truth about capitalism." From 1920-1945, people who knew the truth about capitalism believed what they heard socialism was doing, far away beyond direct observation.

Unfortunately, talking a good line about a workers paradise when there is none doesn't fool people indefinitely. Lenin prescribed what is to be done in order for the working class to triumph over its adversaries. His method can now be seen for what it is: a failure on its own terms. Never mind what the Voice of America says, never mind what the National Chamber of Commerce says, never mind what Joe Mc Carthy says or what Milton Friedman says. Communism is a failure on its own terms. A tightly centralized, highly disciplined party does not insure fidelity to founding principles. It insures fidelity to whoever is in the leading position, whether that is called Chairman or General Secretary. If the man at the top inclines to national socialism, like Slobodan Milosevic, he can provoke the most massive ethnic cleansing since the collapse of the Nazi regime.

There is only one occasion when a communist party central committee had the spine to remove its own general secretary. That was Nicolae Ceauscescu in Romania. There is only one communist party general secretary who has ever been invited to address the luncheon of a national chamber of commerce. That was Chris Hani, in South Africa, and he gave an excellent speech: there will have to be a redistribution, he said, but it cannot be the kind of redistribution where we butcher the cow, everyone takes home some meat, and then there is no more milk. Chris Hani, though, was a man who led by example. People followed him voluntarily. Everyone in South Africa, of every race, creed, color and national origin, would be better off today if he had lived, and had succeeded Nelson Mandela, instead of Thabo Mbeki.

The USA had a rather special negative relationship with communism after World War II. In Europe, South America, some parts of Asia, more often than not, courses on Marxism were taught in universities, which changed nothing. Communists were routinely elected to national legislatures, but always in the minority. However, the U.S. emerged from the war as the world's leading military, economic and diplomatic power, and its closest rival was the USSR. Before WW II, the USSR was the butt of many hostile polemics, but it wasn't viewed as a threat, because the major military powers were Great Britain, France, Germany, and perhaps even the USA. To be a communist and associated with whatever was going on in Russia was not exactly respectable, but, when the USSR emerged as a global rival of the USA, suddenly the association became borderline treasonous. Communists were only prepared, by training, to deal with military rivalries between capitalist nations. This was a new paradigm nobody had prepared for.

In the 21st century, decades after the USSR had collapsed, many in America are suspicious of "the deep state" and rail against "the global elites." Those are legitimate concerns. In fact, both terms refer to what communists used to call "the international imperialist bourgeoisie." Structurally, often in personalities as well, its all about the same concentrations of wealth, power, and sub rosa mechanisms of control. Its not much different from what Jack London set forth in his underappreciated novel, The Iron Heel. But, those who talk about the global elites and the deep state are generally labeled, and sometimes style themselves, as in some sense conservative or right-wing.

We should remember the weavers. Also the miners. Applying everything we have learned the hard way, communist, socialist, social-democrat, anti-communist, whatever... we have all learned some things the hard way. Hopefully we have learned that liberals are part of the problem, not part of the solution. The weavers had the right idea. A man,or woman, who owns no property, who doesn't own his or her own tools, is at the mercy of some high-and-mighty potentate for the right to even earn their own bread by the sweat of their own brow. That is intolerable to any people determined to be free. Since we can't go back to individual craft shops, we need to find ways to get control of our own destiny in a mass-production landscape. We the people need power back in our own hands. Is that communism? Does it matter what we call it? Lenin failed -- the weavers though, had the right idea.

So did our own home-grown American insurgency, the Peoples Party of 1892. Jim Crow was developed in large part to crush the multi-racial, multi-regional challenge that the Peoples Party posed to the ruling elite and the self-styled Two Major Parties. We all have ancestors who could still provide inspiration to where we go from here. The USA remains the nation in the world that has the best historical foundation to build on at this point. It is not a time for despair, but for optimism and perseverance.